We are shaped by place.

Many years ago, I was a consultant for the Welsh government. Part of my assignment required me to visit regional offices in places like Carmarthen and Merthyr Tydfil, which I had only heard of from listening to the football results on Saturday afternoon radio.

These visits involved driving for an hour or so from the Welsh capital city, Cardiff, through the towns and villages of south Wales. Large parts of this are coal mining country - or used to be.

I have a particularly vivid memory of driving through one small town in a fairly narrow valley. One on side was a large graveyard, mainly for miners who had died in an industrial accident. On the other side was a steep hill dotted with trees.

In the bottom of a valley was a cluster of streets made up of terraced housing and the usual conveniences needed for a community. I noticed how many rundown pubs there were and, on one corner, a shabby looking grocery store with black and white signage that simply said ‘SHOP’.

I felt claustrophobic just driving through the valley. Death on one side, scrubland on the other and no view out. In a literal sense, you could not see far beyond the place you lived in without some considerable effort.

I wondered how that might shape a person’s psyche, growing up in a place where the horizons are limited and you’re surrounded by visual reminders of decline, death and what used to be.

Somewhere in my peak football-nerdery (about 12 years ago if you’re wondering), I read an excellent book about Dutch football called ‘Brilliant Orange’ by David Winner. It’s particularly excellent because it’s only loosely about Dutch football.

Sure, it gives a thorough history of Ajax, the Rinus Michels revolution, total football and Cryuff (of course). But what the book is really about is the Dutch culture - why are the Dutch the way they are?

It explores, for instance, the egalitarian streak at the heart of Dutch culture and their football (which has led to some spectacular bust-ups over the years, but that’s another story). And Winner links a lot of this to place and landscape.

The Netherlands, which means ‘low country’, is a fascinating landscape. One-third of the country lies below sea level, protected by dykes and other sea defences. It is also a very, very flat country. Spookily flat, so flat that it feels almost artificial. I’ve travelled through it and the only other place I’ve been to that’s similar is the vast flat prairie lands to the east of Calgary.

Winner, with plenty of research, suggests that this landscape has shaped everything in Dutch culture from their politics and businesses to their art, their music and their sport. Flatness, he suggests, has shaped their relationship with hierarchy.

The landscape also shaped the Dutch perception of space, something he believes was fundamental in the birth of Total Football, a style of play in which any player can play in any position. This creates mesmerising patterns of movement of player and ball into spaces that are only perceived by some and are more like startling murmurations than rehearsed moves. Total Football transformed football forever.

That space and landscapes might influence our very thoughts, feelings and being is not revelatory. And yet, it seems we don’t pay as much attention to it as we might. Culture, both at an individual and group level, is not an inner game - it’s a collective dance between inner and outer realities.

Imagine the headquarters of a global organisation. Any organisation. What comes to mind?

Now picture that the headquarters of this organisation is facing outwards across a vast ocean, something like the Pacific. There is an unobstructed view of the horizon and sunset. That organisation will have a very different culture to one with its headquarters in the heart of a city, surrounded by buildings.

This is also not a radical idea. Indeed, the reason executives and senior leaders usually sit on the top floors of office building is not only to indicate hierarchy but also to symbolically suggest that they see further than the rest of us.

Ultra-modern organisations know this and play with space in new ways. Apple’s HQ in California is a giant, fairly flat circular building apparently designed to replicate the iPhone home button and to symbolise collaboration and equality. And its very location in Cupertino, is flanked by green mountains on one side and not far from San Francisco bay on the other.

In the 1940s, the philosopher Stephen Pepper proposed that there are foundational concepts that shape our reality, how we perceive and interact with the world. He called these ‘root metaphors’, base concepts that allow for the creation of other metaphors that shape our reality.

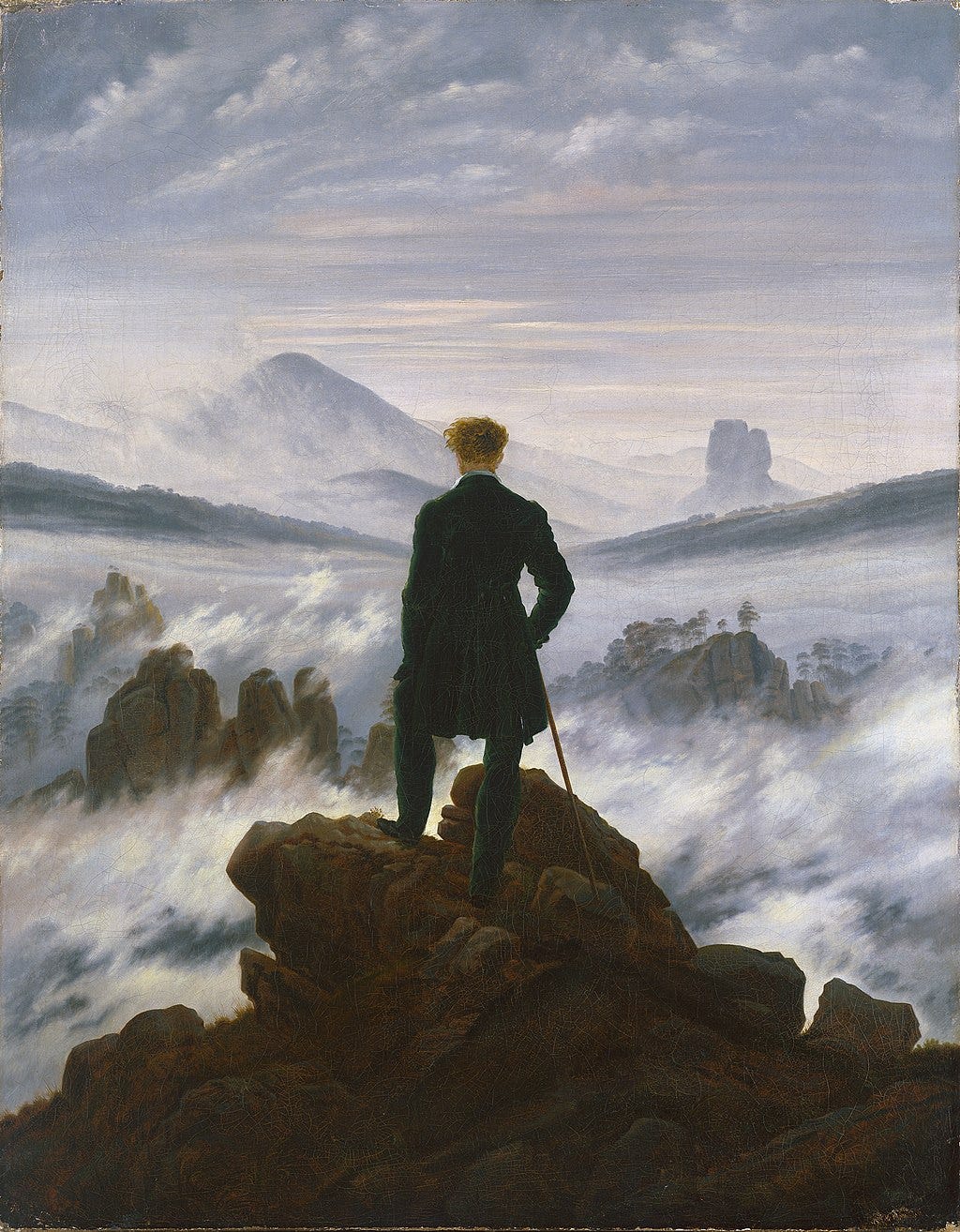

Mountains are a perfect example of this. From the root metaphor of mountains we have developed many other metaphors that shape our world, We talk of conquering, scaling, climbing, peaking, summiting, traversing in contexts like business, sport and our own personal journeys.

In his beautiful history of mountain exploration, ‘Mountains of the Mind’, Robert Macfarlane describes how in the Victorian era, mountains came to symbolise notions like being closer to God and of progress, which must always be upwards and difficult.

Ask someone to draw a simple picture of someone hiking a mountain and they will most likely draw a person walking up a slope that inclines upwards from left to right - this line of ‘progress’ is what we always expect to see on charts representing sales, profit, share prices and GDP.

It remains our desired notion of success but as Seth Godin suggests, progress is not always ‘up and to the right’.

Place, shapes, space, land and what they symbolise are constantly shaping our reality. They shape us.

Most of feel something quite different and pronounced if we’re walking through a forest or looking out to sea. This is not a temporary glitch linked only to the beauty of those natural landscapes. It is a reminder that what we’re surrounded by, influences how far, how deep and how broadly we think, feel and live.

And the more we become aware of the symbols and metaphors we’re immersed in, the more sense we make of the world.

“We construct our models of progression on a gradient. We move on up, or sink back down. It is harder to do the former than the latter, but that makes it only more admirable. One does not, under any linguistic circumstances, progress down. Most religions operate on a vertical axis in which heaven or their analogue of that state is up, and its opposite is down. To ascend, therefore, is in some fundamental way to approach divinity.”

— Robert Macfarlane

Tipping Point: navigating collapse and crisis.

“True hypocrisy, as a kind of lying, is crime. Striking, like all lying, at the possibility of conversation, it risks not only collapsing cooperation, substituting conflict, but worse, maroons us in solipsistic solitary. It’s better to admit your flying is lethal for people who already have nothing, and strive to detox, than claim you don’t fly really and others shouldn’t while strapped into your bucket seat.”

Roc Sandford moved to a remote Scottish island with no running water or people to live on his own. There he wrote a 52-page book, ‘Burnt Rain’, a moving, gorgeous and excoriating polemic about the planet, ecology and the impact we’re having.

About me.

I’m a leadership coach, consultant and facilitator living in Berlin.

Contact me to:

Understand your organisation and its culture as if it were a person, through The Human Organisation framework.

Make sense of what’s going on in your organisation through group dialogues, workshops and strategy sessions.

Make sense of what’s going on with you, your work and your life through my coaching practice.

Have a real conversation.

At the heart of my work is helping individuals and organisations to figure out what is really going on.

You can also find out more about my work with men & masculinity here.

Really thought-provoking piece! I love the exploration of how geography shapes culture and perspective. One thing that stood out to me, though, is the emphasis on landscape as a determining factor in cultural development. While geography certainly plays a role, historical events, politics, and social structures are just as influential. i.e., Dutch football philosophy and egalitarianism likely stem from a mix of history, societal values, and collective struggles—not just the country’s flatness. Perhaps a more nuanced approach would highlight how landscape interacts with, rather than dictates, cultural evolution.

Also, about how we perceive success and progress as 'moving upward' is interesting. It makes me wonder if there are other ways to conceptualize achievement beyond this metaphor—perhaps growth could also be seen as expanding outward, deepening, or even becoming more interconnected rather than just 'climbing higher.' Thank you! :)